Alan Abell also sent this article written by the late, great aviation writer (poet?) James Gilbert. It is too good not to publish.

ROCKFORD, SATURDAY, before the fly-in is really under way.

A few early arrivals are pegged down on the grass like gaudy butterflies in a glass case. All hands are put to raising tents. There is no sign or portent of the Great Lakes I am to fly against Mira Slovak on Wednesday. Sunday is similar, but growing more impatient. Monday the homebuilts start to swarm, bright moths fluttering around the lantern of EAA organization and President Poberezny's personality.Paul Poberezny, Paul, Lieutenant Colonel Poberezny, fifteen thousand hours, holder of seven military ratings, seems a pleasant enough, down-to-earth enough, sane enough fellow when you meet him. You would never guess that the guy is mad. And yet he is, he must be. For he offers his followers a crazy dream, the sort of dream that you and I used to have when we were children—the dream that we could somehow sprout wings from our shoulders and fly, float about in the air over the countryside. Not just Supermen, not just engineering geniuses, not just wealthy playboys, but anybody, you or even 1, we can sit down and build a real airplane, he suggests, and then go and fly in it. He himself, he's built five, and he's flown eighty different ones constructed by other people. Eighty!

The Lakes has at last made it from Texas, and I go up with owner Frank Price for two practice sessions. The Lakes is totally unfamiliar to me, and I have done no real aerobatics for almost a year. Frank shows me a violently square loop, an unbelievable sensation that leaves over six Gs on the clock and has the airplane buffeting on the edge of a high-speed stall at each of the four corners.

Tuesday dawns stiff and painful, with leg and arm muscles (atrophied from a year of Manhattan dissipation) aching from the previous day's workout. Three practice trips: Frank teaches me an out-side avalanche—outside snap on top of outside loop—that goes well with this airplane. We practice snaps and hammer-heads and rolling circles till I am exhausted. This Lakes, with its big barrel of a Warner radial up front, comes down-hill with excessive ease, for a longer dive is needed to gain speed, and kinetic energy is dissipated far sooner, than the slim Stampes I used to fly in England. And the section lines that cut this flat landscape into neat cardboard squares almost make orientation more rather than less difficult.

This great annual get-together at Rock-ford resembles nothing so much as a pre-war Royal Air Force Pageant and Review before King George at Hendon. Indeed, there's King Poberezny himself, driving slowly up and down the ranks of tethered airplanes in his royal red convertible, for all the world like a monarch reviewing his troops.

You look at these airplanes, and you'll see other links with the thirties. Most of the antiques, obviously, actually date from around that time. And the home-bunts use construction methods from that era—spruce, and fabric, and piano wire, and turnbuckles and the like. Indeed, part of the massive technical support King Poberezny gives his followers is the reprinting of ancient manuals, such as CAM 18, abandoned by the FAA in 1959, and the beautiful, beautiful 1932 Flying and Glider Manual.

As an outsider to homebuilding, after you've discovered that the prejudice against wooden structures is either grossly exaggerated or is confined to the uninformed, the next discovery you make is that the reason that prompted most of these fellows to sit down and make themselves an airplane is not so much their love of craftsmanship as the fact that it was simply the cheapest way they could get airborne, and certainly the only way they could get the airplane they wanted.

Wednesday comes far too soon, for Wednesday is the preordained day of the contest. I continue to practice, so far as a 1,500-foot cloud base allows, feeling increasingly forlorn, for those lost two days were crucial, and I am far from fit to be seen in public.

Throughout all the long summer day there is no sign of challenger Mira Slo-vak. Finally, a telegram: he is locked in somewhere in the southwest by huge thunderstorms. Hooray! The contest will be put off, giving me at least an extra day of practice.

But it was not to be; into the Slovak gap gallantly steps North American's Bob Hoover and his P-51, to challenge me in Mira's stead. Bob Hoover, you are a gentleman, but I could cheerfully have murdered you! Before I have time to consider my answer to this David and Goliath contest where Goliath must win, it is announced over the public address system that I have accepted.

So we are committed. Why must Goliath win? Because Goliath Hoover has been flying his show for long centuries of time, in P-51s and F-86s and even F-100s, and it is as polished and perfect a display as you could ever hope for. We agree not to fly a proper competition sequence, but rather a display for the crowd's amusement.

I climb for height and position for the first maneuver. A thousand faces stare up at me, from this height for all the world like a sea of daisies on an English summer lawn. Here we go: push up in half an outside loop, and at 45 degrees to the horizon, heave on left aileron, fully forward stick and right rudder for that outside snap. Disaster! For snap it doesn't, and instead I get three-quarters of a soggy roll that leaves me totally disorientated.

Now any aerobatic pilot will tell you that, if your first maneuver goes awry, you are unlikely to do much better there-after. It is just so on this occasion: my precious height disappears with a rush, and I am forced to abandon even my nice easy rolling circuit half way round when height and airspeed decline below my personal minima. I fill in with inverted runs and hammerheads—pretty enough for the crowd, but hardly advanced aerobatics.

I land. Funny how the ground never does open up and swallow you when you want it to. Bob Hoover flies his usual impeccable, faultless routine and is declared the winner.

The spicy Mexican food at dinner that night in downtown Rockford tastes of the bitterness of defeat. Many people have been kind enough to say they enjoyed watching my flying. Thank you, fans, but it wasn't really good enough for Rockford.

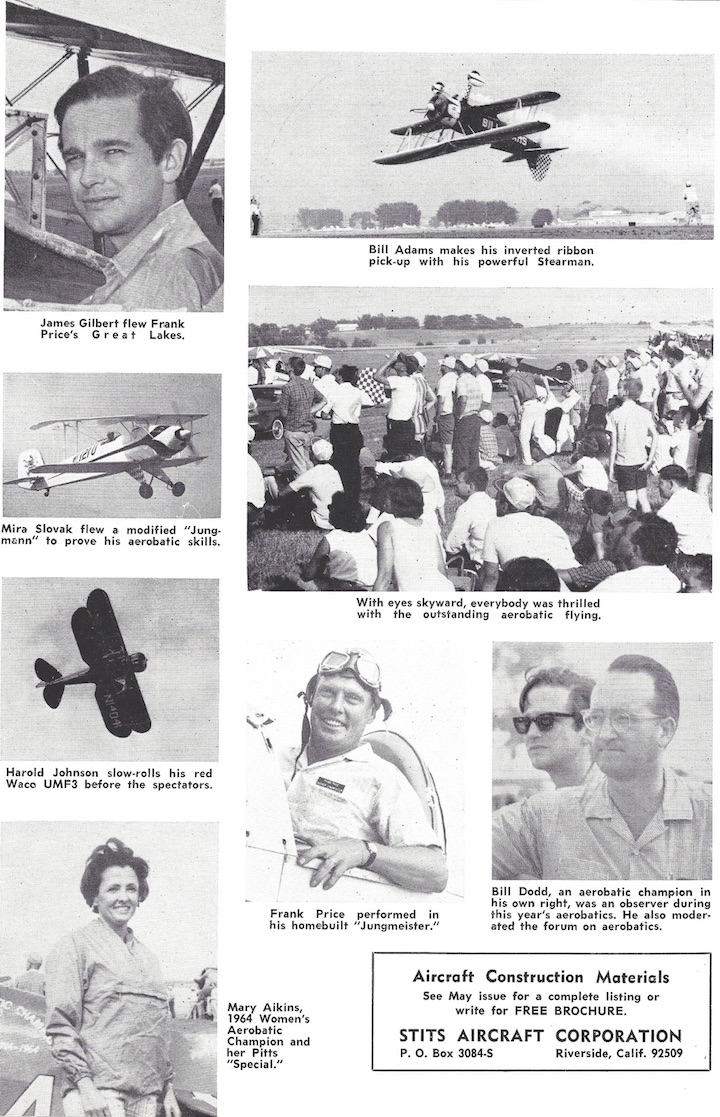

Thursday brings Mira, arriving early in his beautiful black-and-white Jung-mann with its huge 200-hp engine weigh-ing down the nose. We have never met before, and we greet each other with old-world courtesy—Czech on his side, English on mine—in fractured American, he with his splendid Czech accent, me with my BBC Third Programme announcer's drawl. He claims to be even more out of practice than I am—nay, insists this is so. We both depart for hasty practice.

I have been invited to visit neighboring Sycamore field for practice, and, gladly accept, for the air over Rockford is now as busy as a trout stream when the mayflies are rising. Frank in his Jungmeister and I in the Lakes follow an amiable bespectacled gentleman called Bill Dodd (in a beautiful Ryan STA) who claims to know the way.

Sycamore is a revelation. First of all there is someone in a shed building a Sopwith Camel far more beautifully than any Sopwith Camel was ever built during the War To End Wars. Then there is Bill Dodd, who turns out to be the owner of another Ryan and a Jungmeister and doubtless other goodies I did not find out about, who shyly, almost apologetically climbs into one of his Ryans and proceeds to fly a quite flawless aerobatic sequence, carefully devised, of some intricacy and great beauty.

Then there is another bystander, called Bob Herendeen, who has flown all the way from California in his Pitts Special, who equally shyly gets into his airplane and then gives us one hell of a display. His positioning is not so hot, but the things he made that overgrown model airplane do! Lomcevaks in a Pitts are something to be seen, believe you me!

All this talent gathered on some little lost grass strip among the cornfields and bumblebees of rural Illinois! And with these people here, what am I doing fly-ing in the show at Rockford? Perhaps I can quietly slink off home now, before anyone misses me?

Not a chance: I am sent off to practice till my eyeballs turn pink. But the outside avalanche is now a reasonably sure bet, my inside-outside Cuban is going nicely, though I find I need a minimum of 800 feet starting height to complete it comfortably. I do hesitation rolls and hammerheads up and down the strip until they begin to fee! easy, and rolling circles until they begin to look reasonably symmetrical.

Now the old Stampe would even gain a little height during a rolling circle, but this Lakes descends all the way round: I find again that I need initially fully 800 feet to complete it without frightening myself puce.

So, when I come to fly this evening, I may just be able to acquit myself more honorably.

But it was not to be. The powers-that-be of the EAA decided their program is already crowded; only Mira will fly, and they will compare his performance with my dismal exhibition of the day before. Well, it's not a serious competition, so who cares? But I am disappointed. The visibility is better today, and I am on rather better form.

Mira's sequence takes full advantage of his airplane's superb rate of roll and high power-to-weight ratio. (He later told me he can finish an outside loop at the same height he started at, which is a lot better than the Lakes will do.) His flying is nicely within the same area of sky, though rather far away. It is professional, though he is clearly not in practice, and finishes several maneuvers way off line. But there is no doubt that one day, this boy is going to be very good. Indeed, though it is his own airplane, he is almost as out of practice as I am, since he only got the big engine installed just before leaving California for Rock¬ ford. But he has clearly won his challenge.

Friday is getting up at dawn for the chance of flying Mira's airplane before he leaves for Seattle. Is that ever a beautiful flying machine! It has almost all the power you could want for aero-batics, and of course those fabulous feather-light Bucker controls. Rate of roll is almost instantaneous. But I am very conscious of the weight of that big engine up front, particularly when landing, and the airplane must be flown quite gently and carefully round loops, particularly when going outside.

Friday is seeing Mira off, both of us full of self-recrimination at the rotten-ess of our flying, full of determination to meet again, to keep in serious practice in future, even to make The Challenge an annual event. Friday is also a chance to just loaf about, and talk to people, and really relax and watch the air show.

What gentle people these homebuilders are! And how their wives seem to love them! You might think that while hubby was on his way to Rockford they would be at home seeing a lawyer, but not a bit of it—there they are in the camp area pitching tents and setting up the barbecue gear, and as soon as the rain stops there they are out on the airfield holding spanners or wiping off the oil or swinging the propeller for a test-run. In the whole of America there can hardly be a more devoted class of women than homebuilders' wives.

So far as the show is concerned, Bill Adams with his howling great 450-hp Stearman has been making—and stealing —most of the thunder all week. It is a display that for sheer noise and brashness has no peer, full of wild fantastic maneuvers like outside square loops, a triple (wham, bam, slam) snap roll, and an inverted ribbon pickup so breathtakingly low that elegant scarlet rudder is practically ploughing a furrow down the runway. The sheer physical strength needed to throw that big airplane about like that would be beyond most pilots: Bill Adams has huge biceps like a stevedore. Did he have them to start with, or did they grow with the exercise all the years he's been flying this airplane?

This man Poberezny, maybe he's not so mad after all. Maybe he's just stumbled on a great and beautiful yearning of a million quiet people, to make them a flying machine and go fly in it, and maybe he's just sat down to see this yearning gets encouraged and organized, to see that it flourishes as it should. Maybe when everybody makes airplanes and flies, it'll seem so obvious we'll wonder what held it back so long.